Lectures

Please register in advance for this Zoom meeting.

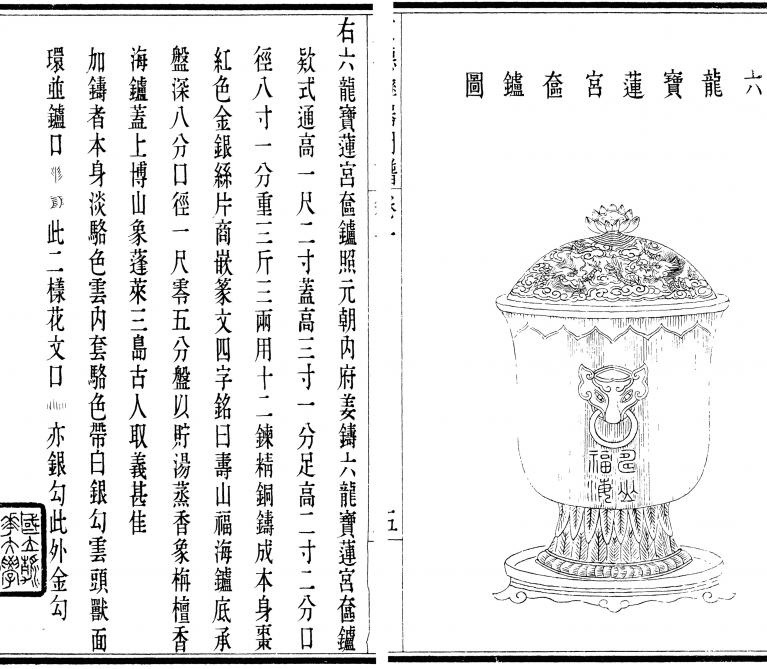

Historians of art in late imperial China are used to working with lists: catalogues of collections, rosters of artists, and checklists of categorized things, often hierarchically ranked. Some were intended for publication, others for personal or official use; some were produced by connoisseurs, some by commercial agents, others by state officials (groups that often overlap). In this presentation I would like to focus on a type of list that has used less frequently in Chinese art history, the inventory of personal goods. In these documents works of art are intermixed with other forms of property, including financial instruments, specie, real estate, bulk commodities, and human beings. The inventories I examine were produced when the property of an official accused of a crime was confiscated, a process that entailed enumeration of each item down to the last scrap of cloth and sack of beans. To accomplish this, local officials and their subordinates had to identify, categorize, and assess hundreds or thousands of items; this could be especially challenging for collectibles such as works of art, antiques, and for items made from precious materials. In this preliminary examination, I ask how Ming and Qing officials, who must have varied in their experience with such objects, might have gone about this work. Then by reading the inventories in comparison with catalogues and connoisseurship guides I suggest that official paperwork was inflected by wider standards of taste and value but maintained a logic distinct from them. First I ask whether the inventories distinguish a category of objects akin to that around which the other types of list coalesce. And at a more granular level, what do the names and properties verbalized by the inventories tell us about what a bureaucrat dealing with a case of national importance thought it essential, and safe, to report about an object of cultural significance.

Bruce Rusk (PhD History, UCLA, 2004) is associate professor in the Department of Asian Studies, University of British Columbia. He studies the cultural history of early modern China (14th to 18th centuries), focusing on cultural practices of authentication and deception, on the history of philology, and cultural uses of writing and books. He has published a monograph on the history of classical scholarship (Critics and Commentators: The Book of Poems as Classic and Literature, Harvard Asia Center, 2012) and a co-translation of a short story collection (Zhang Yingyu, The Book of Swindles: Selections from a Late Ming Collection, with Christopher Rea, Columbia UP, 2017); is a co-editor of the forthcoming Literary Information in China: A History (with Jack Chen, Anatoly Detwyler, Liu Xiao, and Christopher Nugent; Columbia UP, 2021). He is currently writing a study of material and textual forgery in early modern and modern China.