Lectures

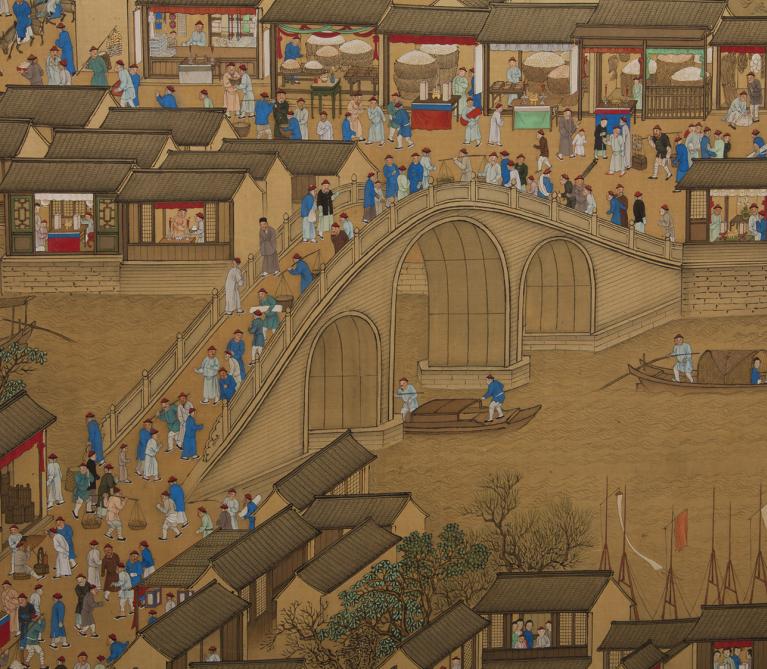

Traditional Chinese panoramic maps remained a standard administrative tool to the end of Imperial rule. However, the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1722) recognized the strategic utility of Western cartography and employed Europeans to survey and map the empire. His successors, Yongzheng (r. 1723-1735) and Qianlong (r. 1736-1795), carried on the practice. During the same period, court artists studied and re-created masterworks in the topographical genre from the Song dynasty (960-1279). The legacy of these traditional paintings could be both useful and poetic, and it informed the well known series of Southern Inspection Tour scrolls commissioned first by Kangxi and later by Qianlong. In panoramas that foreshadow Google Street View, Qing painters recorded a wealth of information while maintaining a link to the classical aesthetic.

In 1744 court officials began the evaluation and cataloguing of the vast palace collection of scrolls and albums, old and new. Their work set the starting point for the study of painting of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Meanwhile, an eager audience in Europe and North America, already keen on Chinoiserie, developed interest in “export pictures” which combined elements of the traditions of China and the West. Although modern art historians were slow to take up the study of Qing painting, the formation of the Palace Museum and the first publications of its collections in the 1930s spurred a general interest that has resurfaced in the last two decades. The challenge remains to sort out the relationship of court painting to private commissions and of scholar-amateur work to that associated with a modern, commercial art market.

Publishing flourished in the late Ming period and then again shortly after the Qing conquest in 1644, despite the destruction of important publishing houses in several cities during the turmoil of the fall of Ming. The sophisticated simplicity of traditional Chinese printing techniques – with no presses needed – made small-scale publishing workable and trade in books expanded. Books were exported to Japan on ships with other cargoes. Old books were collected with enthusiasm. The Qianlong emperor’s great literary compilation, the Siku Quanshu (Complete Library of the Four Treasuries), now a scholarly resource available and searchable online, was made possible by the cooperation of private book collectors. Books were also available on a popular level and were sold from floating vessels on the Southern waterways. The popularity of printed books continued to the end of the Qing dynasty, despite the destruction of many printing houses during the Taiping Rebellion. A rapid transition to lithography began in the late 1870s. Throughout the period, painting manuals and illustrated literary works circulated widely, inspiring new trends in painting.