Lectures

Korea, because of its geo-political situation, was a natural recipient of the most advanced Chinese art and culture, which were then transmitted to Japan. This process of transmission, however, stimulated the development of a distinctive Korean national and cultural identity, along with the creation of works of art in a wide range of mediums that are uniquely Korean in every aspect. Examining Korean art in the larger context of East Asian history, culture, and artistic production, this lecture will explore how this process evolved over more than a thousand years and shaped art that is unmistakably Korean in iconography, form, color, style, and technique.

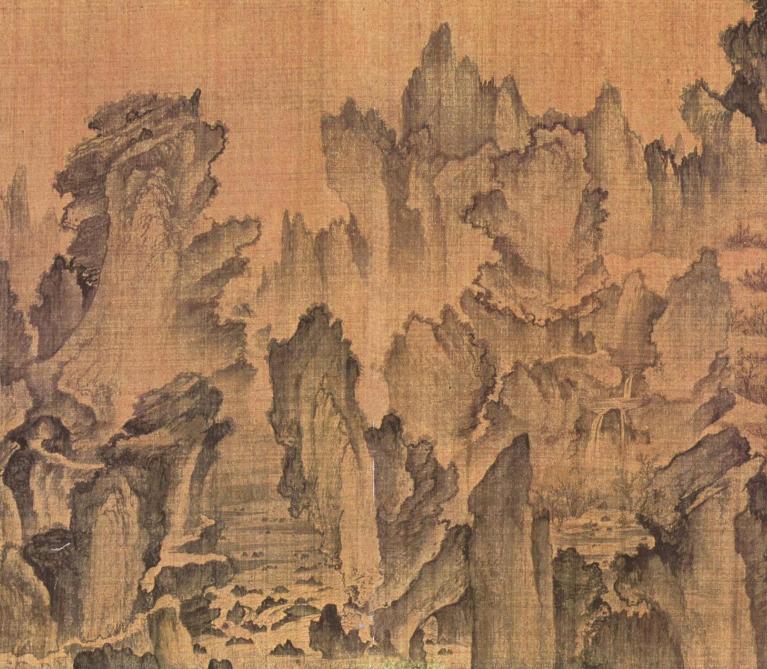

After the fall of the Ming dynasty (1644), Koreans became increasingly conscious of their own cultural identity, investigating not only their historical and cultural heritage but also the exceptional beauty of their land. The genre of “true-view” landscape painting—depictions of scenery that actually existed in Korea—flowered in the seventeenth century and continued through the beginning of the nineteenth. Its origins coincided with the beginning of the School of Practical Learning in Qing China, which Korean scholars avidly absorbed and assimilated into their own cultural environment. It was against this multi-layered cultural and intellectual background that “true-view” landscape painting evolved. This genre of landscape can now be recognized as the Joseon dynasty painting that best expresses the unique inspiration, creative energy, and ethos of the Korean people.

Unlike most landscape painting of the Joseon dynasty, which was done in ink or ink and light colors, the screen paintings produced for and used in Korean palaces were mostly executed in brilliant colors. Because Korean art-historical research during the twentieth century focused almost exclusively on literati ink paintings, these colorful screen paintings have been relegated to a “lesser” category of art and have sometimes been labeled “folk paintings.” However, recent studies of uigwe royal documents, as well as other literary and historical sources, have shed much light on the identification of the themes of palace screen paintings and their specific functions within various state rites. This research has also led to revealing investigations of the symbolic meanings of the palace screens. This lecture will demonstrate how securely dated documentary evidence such as uigwe “re-position” the colorful screen paintings of the Joseon period.