Lectures

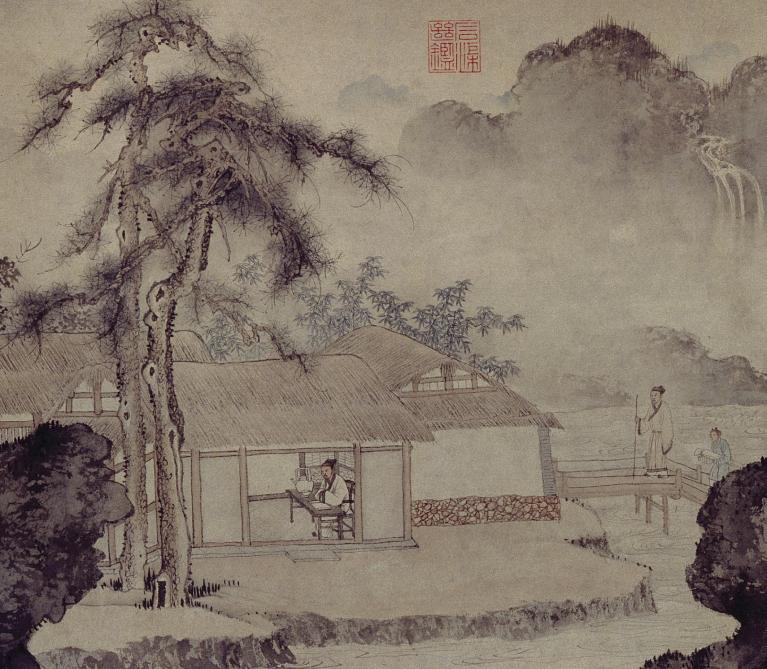

Commemorative landscape painting is distinguished from the monumental painting that preceded it in the Song by the intention to celebrate a particular historical person, to make known his creditable achievements, and to win social status and recognition. This is an art of disguised portraiture in which the subject asserts himself, his ambition, and tastes, openly seeking acceptance and support from his peers. The value system of the literati social structure was so familiar to its members that the individual could address his audience through pictorial biography just as he had through literary biography for centuries. The setting for such pictures is always natural landscape, interpreted in many different moods and forms, but the landscape is secondary to the man, and its true function is to mirror him as the humanistic ideal of the recluse-scholar. The literary baggage attached to the new landscape increased during the Yuan dynasty, when the first commemorative paintings appeared, and flourished through the Ming, producing an art form that was simultaneously pictorial and verbal. This art was a direct descendant of the “social biography” of the past—eulogies, poems, prefaces—communicating personal experience to other men. It was also a direct descendent of Song and Yuan landscape styles now turned into a new world.

A sub-type of commemorative painting concerned the biehao picture, name picture, which has much to say about the subjective nature of Chinese painting in the later dynasties. Chinese men had several names for use in different circumstances—family, formal, legal, and social. The biehao was a brush name, sobriquet, the only name he chose himself, and was chosen for reasons which only he knew. It was intended to set him apart from others, to convey something about him which was private and personal but which, nevertheless, the owner desired to be known to his class at large. It might be poetic, allusive, ironic, fanciful in many ways, but it was often concretely figurative and so could be illustrated in visual form. The earliest biehao paintings appear in the Yuan dynasty and reached their peak of popularity among Suzhou art patrons in the Ming dynasty. They flourished at a time when literati circles deplored literal illustration and sniffed at realism. They escaped both by hiding the identity of the owner in the colophons attached to the painting, one of which was a preface (xu) or explanation (bian) divulging the owner’s identity and explaining how he acquired his hao. The picture was constructed around a conundrum from the start and afforded the patron and painter both ample opportunity for the play of wit, irony, double meanings, and other anomalies more often associated with the world than with the image.